Intersectional Approaches to Women’s Suffrage: Incorporating Marginalized Perspectives

Author: Jessa Nootbaar

Subject: History

Topic: Integrated; Women’s Suffrage Movement

Grade Levels: Middle School: 8th Grade

Overview:

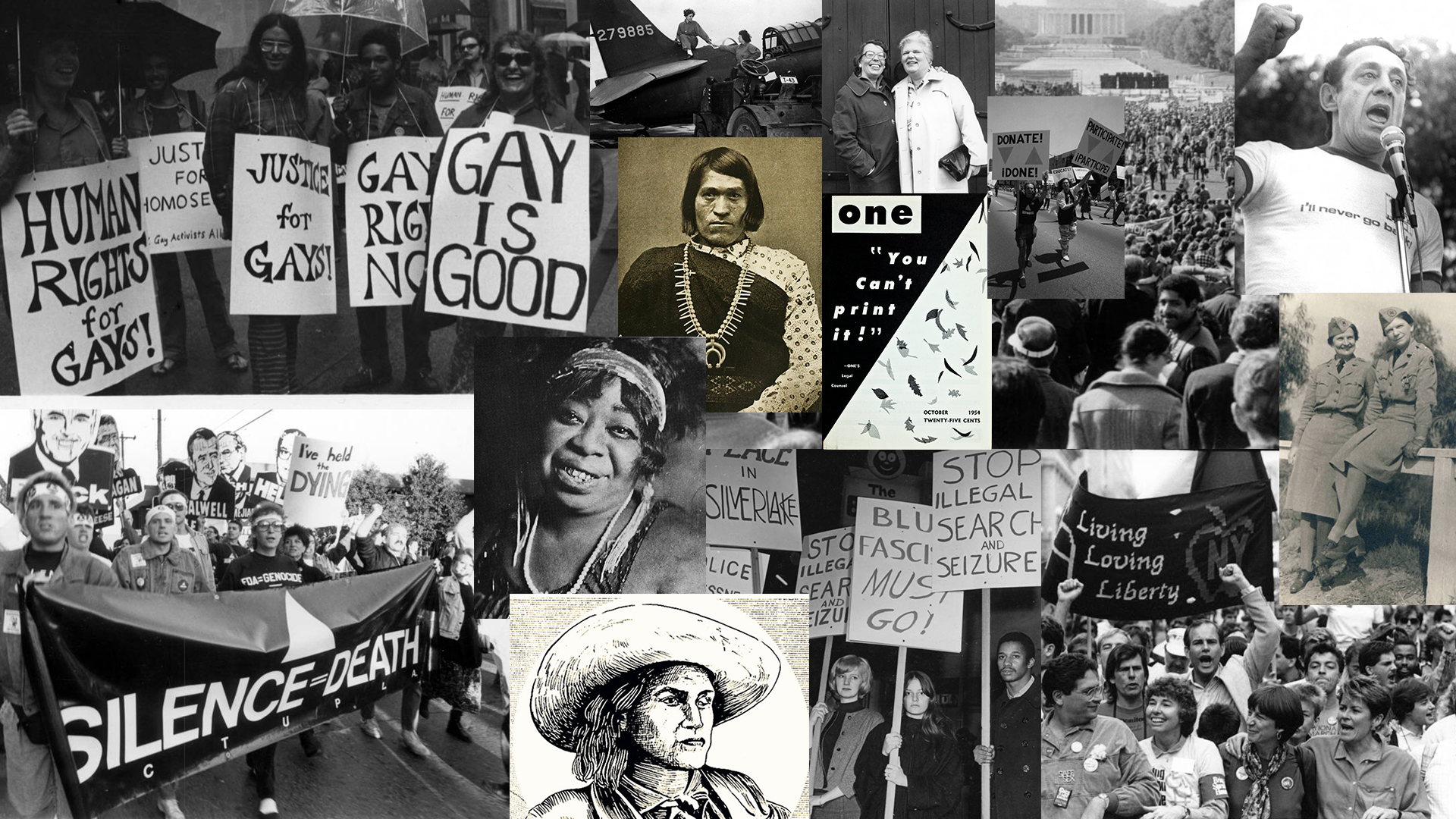

This lesson explores the Women’s Suffrage movement through a speech given by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, a Black suffragist and abolitionist, who critiques the largely white and middle class movement for its narrow perspective that ignores the country’s pressing race and class problems. This lesson introduces perspectives and realities often ignored in the general curriculum on Women’s Suffrage.

Time: 55 minutes

Lesson Plan Resources:

Lesson Objectives:

- Understand the complexities around race, gender, and access to voting, including the fact that not all women were granted suffrage at the same time.

- Explore the political and social climate in the post-Civil War U.S.

- Encourage students to think critically through an intersectional lens.

Essential Questions:

- Who participated in the Women’s Suffrage movement?

- Who did the Women’s Suffrage movement benefit?

- Who did the Women’s Suffrage movement neglect?

- What was the social and political climate in the post-Civil War U.S.?

Standards:

HSS 8.6 Examine the women’s suffrage movement (e.g., biographies, writings, and speeches of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Margaret Fuller, Lucretia Mott, Susan B. Anthony).

CCSS RI 8.2 Determine a central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to supporting ideas; provide an objective summary of the text.

CCSS SL 8.1 Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with diverse partners on grade 8 topics, texts, and issues, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly.

HISTORY FRAMEWORK: CH 12 P 252 Out of these far-reaching reform movements of the nineteenth century, Americans became increasingly interested in discussing the status of women. Students may begin with a brief review of the legal and economic status of women and learn about the major impetus given to the women’s rights movement by leaders such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton… What did freedom mean, and how did it change over time? Noting the intersections between previously studied reform movements, the women’s rights movement, and the abolitionist movement, students can study the efforts of educators such as Catharine Beecher, Emma Willard, and Mary Lyon to establish schools and colleges for women.

HISTORY FRAMEWORK: CH 12 P 269 Students also explore the impact of Reconstruction on African American kinship structures and family life.

Vocabulary:

Women’s Suffrage: The legal right of women to vote in public elections.

Suffragist: A person who advocates for women’s suffrage (not to be confused with suffragette, a woman who advocates for women’s suffrage through more militant tactics).

Intersectionality: Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, intersectionality refers to an analytical framework that views people through the interaction of their social identities (including gender, race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic class, etc.) resulting in a unique lived social experience of oppression and privilege, as opposed to an additive model of oppression that views people as the sum of their social identities.

Black Suffrage: The legal right of Black people to vote in public elections.

Voting Accessibility: The ability of people to exercise their right to vote.

Citizenship: The state of being legally recognized as a subject of a nation; can come with certain rights, including voting, but sometimes not.

Dred Scott Decision: The ruling of the US Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857 that declared Black people were not American citizens and had no right to bring lawsuits.

Teacher Background:

For more on Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of intersectionality see: https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/mapping-margins.pdf

Materials:

- Computer

- Projector

- Speech Handouts

Instructions:

Introduction (10 minutes)

- Students may have already begun to study the Women’s Suffrage movement; tell them that they will be examining the movement from a different perspective- that of a 19th century Black female activist.

- Explain to students that while they may know that the 19th Amendment, which didn’t allow voting discrimination on the basis of sex, was passed in 1919 and instituted in 1920, but some people, including women, did not have or were not able to exercise their right to vote for years/decades after. For example, Native Americans were not granted the right to vote until 1924, Asian Americans were not granted the right to vote until 1952, and many people of color, regardless of legal right to vote, were prevented from voting by white Americans. The Voting Rights Act, signed in 1965, was created to protect Black American’s right to vote.

- Introduce the time period and context. Ask students to think about what is happening and has just happened in the country in 1866.

- Consider discussing the following:

- In April, the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was passed and intended to establish protections for all American citizens, including Black Americans and formerly enslaved individuals.

- Important Note: Black men did not yet have the right to vote- they would be legally granted it 4 years later with the ratification of the 15th Amendment, which says that voting cannot be denied on the basis of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” When Harper gave her speech in 1866, there would have been debate about Black Suffrage, including within the suffragette community. Some suffragettes supported Black Suffrage and some opposed it, feeling that white women should be granted the right to vote before Black men. Additionally, some women’s rights groups didn’t allow Black members.

- The Civil War had ended one year before in 1865, with Union victory.

- Three years before, in 1863, Lincoln (who had been elected in 1860) had signed the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all enslaved people free, though many Southerners did not obey this proclamation at first.

- In 1857, the Dred Scott case (which Harper references) had declared Black Americans to not be American citizens, with no right to bring lawsuits to court.

- The Seneca Falls Convention, the first American women’s rights convention, had taken place 18 years before, in 1848.

- There were many questions as to who was truly considered a citizen and what rights citizenship entailed. Both women and Black Americans were thinking about these questions.

- Consider discussing the following:

Speech analysis (40 minutes)

- Give students 15 minutes to read (or have volunteers read aloud) France Ellen Watkins Harper’s speech, “We Are All Bound Up Together” (1866)- The handout includes background on Harper and instructions for active reading.

- When students are finished reading, check for understanding by asking students to:

- Explain Harper’s main argument (e.g. that while she does support women’s suffrage, she recognizes more pressing issues of race and class that are likely to be ignored by the majority white, middle-class women’s movement who are working to benefit people like them)

- Ask students what emotions they think Harper was trying to convey. How might her speech have been presented? With what tone of voice? With what emphasis?

- Allow time for students to ask clarifying questions regarding parts of the speech they didn’t understand. Make sure students catch Harper’s references to segregation, Dred Scott case, the Civil War, Harriet Tubman, etc.

- Ask students to pick one short quote they found most compelling or interesting. When they have chosen a quote, they can discuss why they chose this quote and what they think it means with a partner or in groups of 3.

Group discussion (5 minutes)

- To conclude, give the class an opportunity to discuss what they learned. Consider the following questions:

- Whose stories do we hear when learning about Women’s Suffrage?

- Why is it important to hear the perspective of someone like Frances Ellen Watkins Harper?

- What did you learn today that you didn’t know before?

- What do you think social movements can do to be inclusive of all people?

Assessment

Have students imagine that they were at the 1866 Women’s Rights Convention and heard Harper’s speech there. They should write a letter to Harper, detailing what they think the next steps for the Women’s Suffrage movement should be. Their ideas should be supported by excerpts of Harper’s speech or historical happenings. Make sure students stay “in character” and don’t refer to events or technologies that did not yet exist in 1866.

Relevant Resources:

Chughtai, Alia. “Who got the right to vote when?” Al Jazeera Interactives, Al Jazeera, 18, Aug. 2020, https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/2016/us-elections-2016-who-can-vote/index.html.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color”. The Public Nature of Private Violence, edited by Martha Albertson Fineman and Rixanne Mykitiuk, New York: Routledge, 1994, pp. 93-118.

Dionne, Evette. “Women’s Suffrage Leaders Left Out Black Women.” Teen Vogue, 18 Aug 2017, https://www.teenvogue.com/story/womens-suffrage-leaders-left-out-black-women.

Ginzberg, Lori D. “For Stanton, All Women Were Not Created Equal.” NPR, NPR, 13 July 2011, www.npr.org/2011/07/13/137681070/for-stanton-all-women-were-not-created-equal.

Harper, Frances Ellen Watkins. “We Are All Bound Up Together,” in Proceedings of the Eleventh Women’s Rights Convention. New York: Robert J. Johnston, 1866.

Lange, Allison. “National American Woman Suffrage Association.” History of U.S. Woman’s Suffrage, National Women’s History Museum, 2015, www.crusadeforthevote.org/nawsa-united.

Pascaline, Mary. “Voting Rights 2016: When Did Women, Black People And Native Americans Get The Right To Vote?” International Business Times, Newsweek Media Group, 5, Dec. 2020, www.ibtimes.com/voting-rights-2016-when-did-women-black-people-native-americans-get-right-vote-2440441.

Author Information

Jessa Nootbaar is a Summer 2018 Education Curriculum Intern at Our Family Coalition in San Francisco, CA, and a Sociology student at Barnard College in New York, NY.