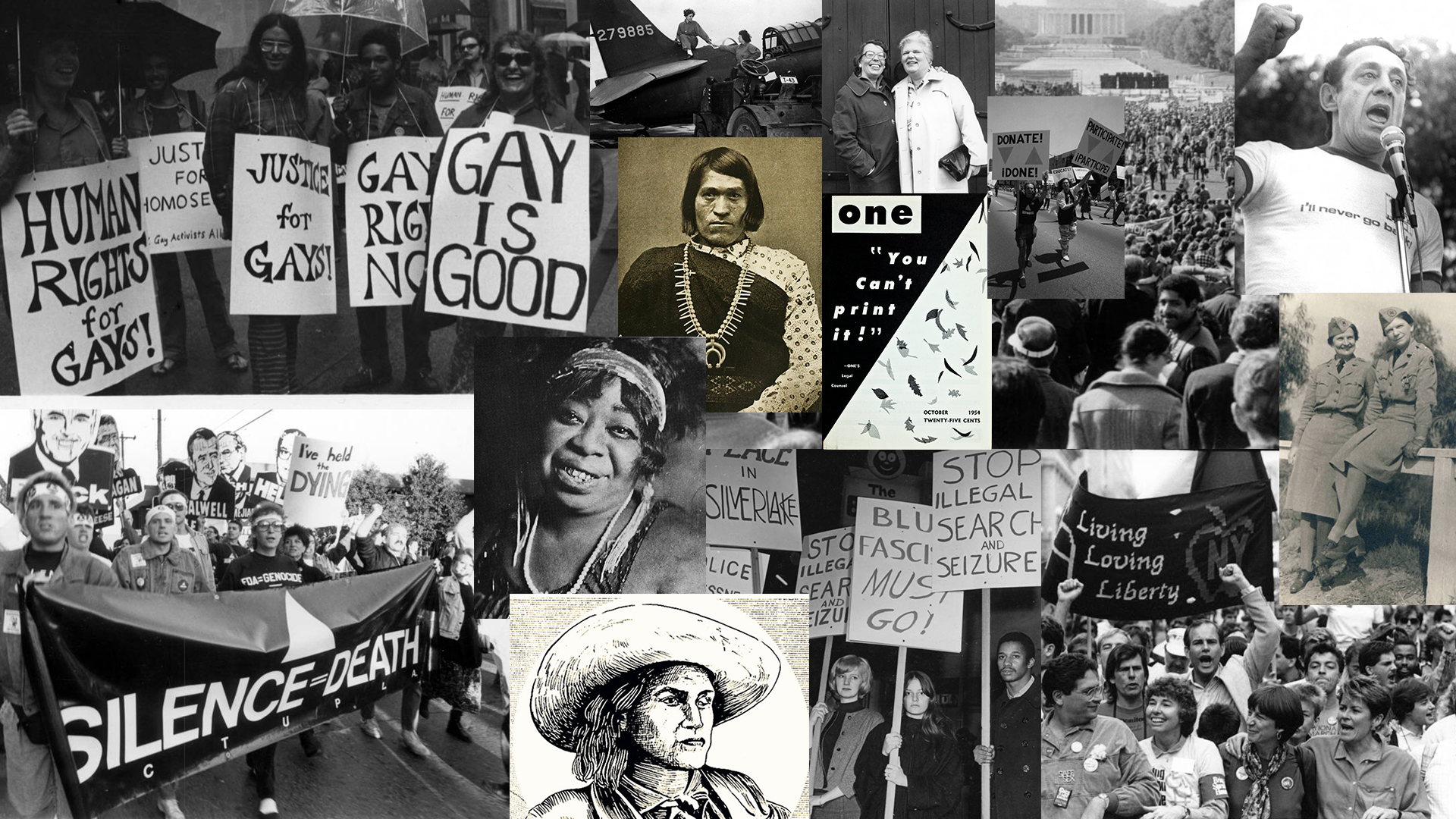

When looking at present-day media and past historical records, transmasculine* people appear to be disproportionately underrepresented. Transmasculine individuals have struggled for visibility and recognition, as demonstrated by the lack of representation in the media and popular culture today. Most trans characters on TV and in movies are women, and the attention toward trans issues has primarily centered on transfeminine people and experiences. A glimpse into trans history reveals a scarcity of documented lives of transmasculine individuals, their stories contested, erased, ignored, or still waiting to be uncovered. The reasons behind this phenomenon are nuanced and complex and continue to be theorized today. This piece will attempt to illuminate explanations behind transmasculine invisibility and shed light on the lives and experiences of transmasculine folks, both in the past and present.

*I use the umbrella term “transmasculine” to refer to individuals assigned female at birth who lean toward or identify with masculinity. This encompasses both trans men and nonbinary people and is a more inclusive term than just “trans men.”

Note to readers: This article focuses on Western experiences and understandings of gender and sexuality, as the most accessible scholarship on historical transmasculine experiences is U.S.- and Eurocentric. This article does not cover the breadth of diversity of gender-nonconformity and expansiveness for individuals and experiences in non-Western societies and cultures.

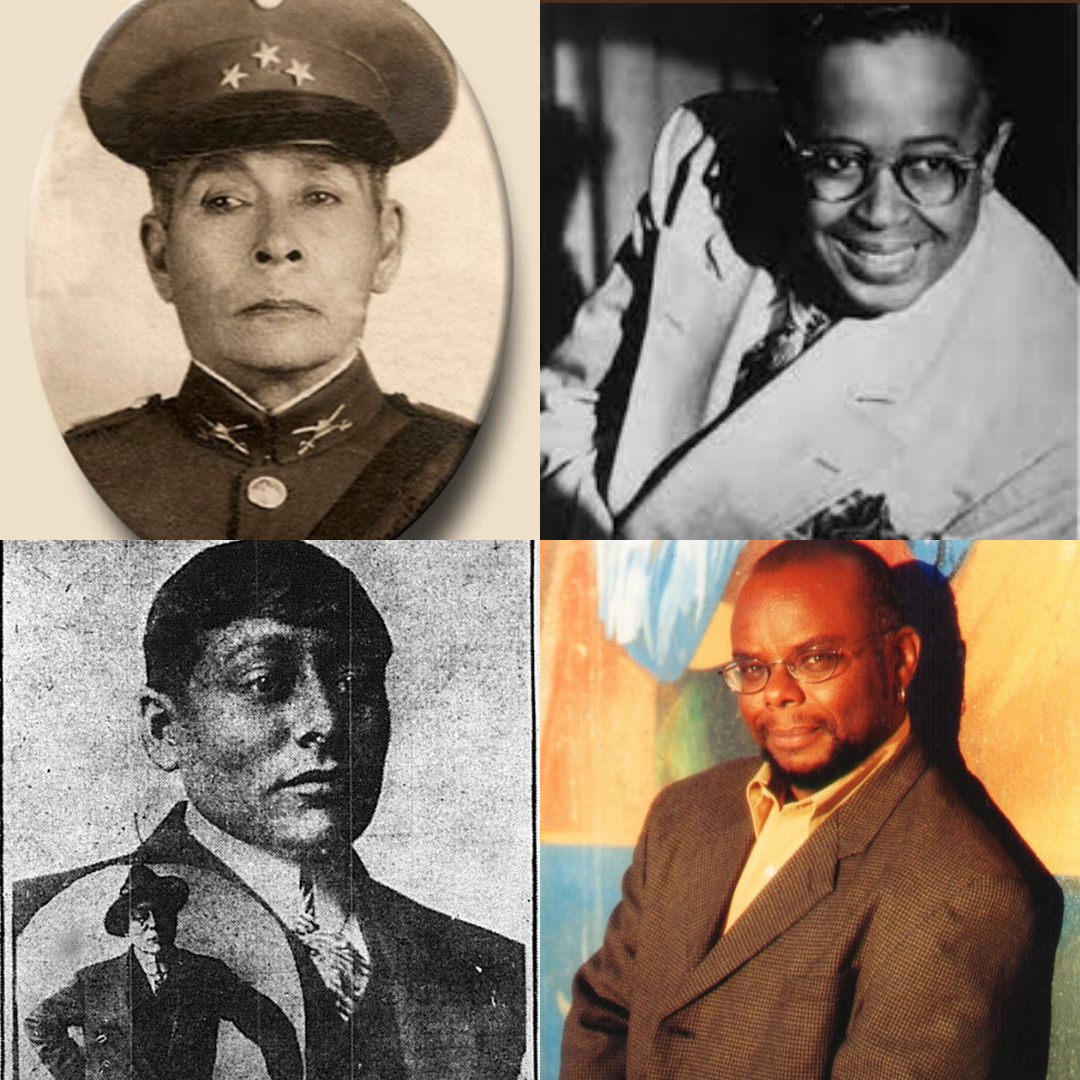

Transmasc BIPOC in History Fig. 1:

Amelio Robles Ávila (1889-1984) was a Mexican transmasculine person and decorated colonel during the Mexican Revolution. He has since been recognized as a male hero of the Mexican Revolution. Ávila lived openly as a man from age 24 until his passing at 95.

The Complexity of Trans History

When looking at the past, labeling historical figures as “trans” can be complicated. Gender as a social category is unstable and has shifted over time across cultures and geographies. Our definitions of “sex” and “gender” are also socially constructed; even “cis man” and “cis woman” are modern categories (Heyam). While the contemporary terminology for transness is relatively new, trans experiences are not. We can conceptualize trans experiences of the past not by their modern definition—an individual aligning with a different gender than their birth assignment—but as a transgression, a movement, or a malleability of gender. Even the modern definition of “trans” as a category cannot be applied universally in history. In England and Wales, for example, birth records did not widely include a gender marker before the nineteenth century (Heyam). Further, in the mid-20th century, “gender” and “sex” were interchangeable terms; we cannot even accurately apply our contemporary categories of “man” and “woman” to describe people of the past (Heyam). Our understanding of gender is dependent on personal, cultural, and historical factors, demonstrating the fact that every individual’s experience with gender is unique (Heyam). Even though we cannot impose modern identity categories onto people of the past, individuals’ experiences can still be considered trans and as part of trans history, as they embodied a movement across or beyond gender.

Transmasculine BIPOC in History Fig. 2:

Wilmer “Little Axe” Broadnax (1916-1992) was a Black transmasculine person and American gospel quartet singer during the golden age of traditional Black gospel in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. He lived as a man and remained stealth throughout his life; his assigned sex was only discovered after his death.

Race, Gender, and Masculinity

Moreover, the most mainstream, well-known, and accessible trans histories are the seemingly simple ones—individuals who lived consistently as a different gender, who lived relatively recently, who pursued medical transition, and who have provided first-hand testimony of their gender identity (Heyam). Our understandings of gender are inextricable from race as well. Trans people able to perform white femininity or masculinity are taken most seriously, while trans people of color continue to be marginalized (Heyam). This leads to the point that our trans histories are predominantly white. Colonial ideals of binary gender influence historians telling history, and racism impacts whose stories are uplifted and centered. In addition, trans individuals who can conform to white femininity or masculinity have effectively influenced contemporary notions of transness (Heyam). Resultantly, whiteness is also privileged as the primary identity category for transgressing gender, further marginalizing people of color who have transed gender (Manion).

For transmasculine individuals, this connects gender transgression to the aspiration for white manhood. Like the wider category of gender, the idea of “manhood” has been defined differently in different times, places, and cultures (Bedermen). The noun “masculinity” only became popular by 1890 and had distinct and since forgotten connotations (Bedermen). In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the reifying of male power was closely linked to whiteness, as male power stemmed from white supremacy (Bedermen). This proves the inseparability of race and gender as identity categories, as well as the invisibilization of narratives and histories of trans BIPOC.

Transmasculine BIPOC in History Fig. 3:

Ralph Kerwineo (1876-1932) was a Black and Indigenous transmasculine person and nurse who became known after his ex-wife, Mamie White, revealed his “true sex” to the local police. Kerwineo was arrested for disorderly conduct, harassed while in custody, and forced to live as a “woman” thereafter. Kerwineo’s story of police violence is one of many instances of racialized gender deviance. His intersectional identity made him more vulnerable to hatred, harassment, and brutality. This legacy of racism, transphobia, and violence extends to today.

Gender, Sexuality, and Transgression

Some of the more accessible transmasculine histories are documented in Jen Manion’s book Female Husbands—the term encompassing individuals assigned female at birth who lived full-time as men and entered what appeared to be (legal) heterosexual marriages with women. This term was prevalent in the U.S. and U.K. from 1746 to the mid-20th century. This phenomenon was relatively easily digestible by wider society, as most people assigned female at birth lacked access to economic mobility, education, or legal autonomy (Manion). In other words, no one was surprised when “women” desired to access the privileges granted to men, especially those of white men. In early modern Europe, narratives of people assigned female at birth who wore men’s clothes and joined the military were common (Manion). Charles Williams of New England is one of the few documented African Americans assigned female at birth to live and work as a seaman. In juxtaposition to white transmasculine individuals attaining white male privilege, Black people assigned female at birth commonly transgressed gender to escape the violent system of enslavement (Manion). This demonstrates the deep-seated connection of gender and race, both social constructions shaped by one another, as well as the distinct experiences of gendered and racialized bodies.

Moreover, these stories of female husbands are contested as lesbian rather than trans history. Scholar Jack Halberstam states, “While it is true that transgender and transsexual men have been wrongly folded into lesbian history, it is also true that the distinctions between some transsexuals and lesbians may at times become quite blurry” (Manion). Parsing the distinctions between lesbian and trans history can be tricky, contributing to the obscuring of transmasculine stories. We cannot know how these individuals would identify today according to modern categories; however, female husbands paved the way for future disputes and rejections of the category of woman, its associated norms and roles, and expected relationships with men. Describing an experience as “trans” is not analogous to labeling a historical figure as “trans.” The latter imposes a contemporary identity category, while the former allows for observation, exploration, and analysis of lived experiences relatable across time and place.

Transmasculine BIPOC in History Fig. 4:

Alexander John Goodrum (1960-2002) was a Black, bisexual, and disabled trans man, as well as a civil rights activist, writer, and educator. His involvement in LGBTQ organizing and advocacy work spanned decades, including founding TGNet Arizona, a Tuscon-based transgender advocacy organization. He unfortunately died by suicide in 2002 and was awarded the Godat Award after his passing.

The Privilege of “Passing”

So where are all of the transmasculine people? One possible explanation lies in the privilege of “passing” for many transmasculine individuals. “Passing” is a colloquial term used to describe the experience of being perceived as cisgender (non-trans). Transitioning for transmasculine folks—which can often include taking testosterone, a form of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy (GAHT)—can result in transmasculine individuals being societally perceived as non-trans, or more specifically, as cis men. With this different perception comes male privilege, providing access to advantages granted to men based on their sex. This experience can be easier than that of transfeminine individuals (particularly for white, nondisabled, and non-Queer transmasculine folks). As transmasculine folks gain access to male privilege, transfeminine people become targets of transmisogyny—a term coined by scholar Julia Serano that pinpoints the intersection of transphobia and misogyny that transfeminine individuals experience. Resultantly, transmasculine people often can “disappear” into mainstream society, situating them as less vulnerable to overt transphobia. Thus, there is sometimes not as much of a need or desire for trans community.

The concept of “passing” is prevalent in history as well. According to Emily Skidmore in their book True Sex, transmasculine people in history frequently passed as “conventional men” and often desired to conform to normative community values. In the 20th century, transmasculine individuals tended to live in small towns instead of big cities. White privilege and white-passing privilege provided the ability to blend in more easily. Despite their ability to “pass” as conventional men, many transmasculine individuals’ “true sex,” as termed by Skidmore, were revealed following their deaths. Skidmore states that “At least 65 cases of reported stories of individuals assigned female at birth but chose to live as male appeared in U.S. newspapers between the 1870s and 1930s” (2). While these records of transmasculine individuals in history exist, they are predominantly white and within the last two centuries.

Sensationalized Stories

Another potential reason for transmasculine invisibility is that transmasculine people are harder to sensationalize than transfeminine people. Individuals and wider society have trouble understanding why someone would give up their male privilege; conversely, it is easier to comprehend why someone would “want” to be a man. Along the same lines, Western society is more likely to accept “masculine” women than “feminine” men. Masculinity is a privileged and desirable attribute in our Western cis-heteropatriarchy; femininity is predominantly viewed as weak and subordinate. With greater visibility, like that ascribed to transfeminine individuals, comes a greater risk of facing harmful stereotypes, ridicule, and violence. This is evident because most trans homicide victims are transfeminine people and trans women, most notably BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) trans women. While the invisibility of transmasculine people grants them myriad protections, it also damagingly obscures transmasculine experiences, past and present.

Transmasculine Folks Today

Transmasculine histories continue to be obscured and invisibilized today. This phenomenon can be attributed to the privilege of “passing,” especially for white individuals; ever-changing definitions and understandings of gender and masculinity; the complexities of telling trans history; the inextricability of gender from race; and the ongoing marginalization of BIPOC narratives. Trans history as a subject area is unstable, though observing past experiences as trans can be powerful; people who came before us demonstrated the possibilities and expansiveness of gender. Transmasculine individuals today continue to break boundaries and push forward our ongoing movement for liberation. Below are a few notable contemporary transmasculine BIPOC.

Schuyler Bailar is a Korean-American trans man, author, educator, and activist. He is the first openly trans athlete to compete in any sport on an NCAA Division 1 men’s team.

Kylar W. Broadus is a Black trans man, attorney, long-time activist, author, and professor. He founded the Trans People of Color Coalition, the sole national organization dedicated to advancing the civil rights of BIPOC trans people. He was also the first trans American to testify in front of the U.S. Senate in favor of the Employment Nondiscrimination Act.

Laith Ashley is an openly trans man of Dominican descent and a model, actor, and activist who has made waves in the modeling industry.

Patricio “Pat” Manuel, also known as “Cacahuate,” is a Black trans man and the first trans male boxer to fight professionally in the U.S. In 2016, he became the first trans man to defeat a cis man in the amateur male division.

Myriad others are working to increase visibility and fight for trans rights. Our trans ancestors paved the way for us to live authentic lives. It is our responsibility to honor them. They are not lost, erased, or forgotten; they are still here, standing with us in the battle for our lives.

Works Cited

Abel, Jillian. “10 Black Trans* Activists You Should Know.” Medium, 7 Feb. 2020, medium.com/tmi-consulting-inc/10-black-trans-activists-you-should-know-ec69464f66e9

“Alexander John Goodrum.” Wikipedia, 21 July 2023, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_John_Goodrum. Accessed 24 Aug. 2023.

Bederman, Gail. Manliness and Civilization. University of Chicago Press, 7 Apr. 2008.

“Celebrating Black TGNC History | SAGA.” Sagatucson.org, 1 Feb. 2021, sagatucson.org/news/celebrating-black-tgnc-history.

Cvetnic, Nicole L. “9 Transgender Men of Color You Should Know.” The Root, www.theroot.com/9-transgender-men-of-color-you-should-know-1790860386.

“FTM Contributions in HIStory.” Web.archive.org, 18 Jan. 2015, web.archive.org/web/20150118084516/www.computerconsultingservices.net/mensworld/images/FTMHistory.htm.

“FTM History – Brief History of FTM Trans Civilization – TransGuys.com.” TransGuys.com, 29 Oct. 2012, transguys.com/features/ftm-trans-history.

Heyam, Kit. Before We Were Trans. Seal Press, 13 Sept. 2022.

Manion, Jen. Female Husbands: A Trans History. Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, NY, Cambridge University Press, 2020.

“Patricio Manuel.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 20 Feb. 2019, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patricio_Manuel.

“Primary Source Set: Trans Men.” GLBT Historical Society, www.glbthistory.org/primary-source-set-trans-men.

“Ralph Kerwineo.” Wisconsin Historical Society, 10 May 2021, www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS16568.

Roberts, Monica. “TransGriot: Alexander Goodrum-Gone Ten Years.” TransGriot, 28 Sept. 2012, transgriot.blogspot.com/2012/09/alexander-goodrum-gone-ten-years.html.

Skidmore, Emily. True Sex: The Lives of Trans Men at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. New York, New York University Press, 2019.

ubleproject. “A Tenor Passes: Wilmer Broadnax.” Tumblr, ubleproject.tumblr.com/post/29515613795/a-tenor-passes-wilmer-broadnax.

Villarreal, Daniel. “Get Inspired by These 5 History-Making Trans Men Who Defied the Odds to Live Authentically.” Queerty, www.queerty.com/get-inspired-5-history-making-trans-men-defied-odds-live-authentically-20220424.